Every October, London becomes the barometer of the world’s metal economy.

The LME Week — the traditional convergence of producers, traders, financiers, and consumers — is where the industry tests its pulse.

Yet this year, the reading was not cyclical but civilizational.

Behind the debates on copper deficits, premiums, and TC/RCs lies something larger: a reordering of how nations think about metals, production, and power.

For two decades, analysts spoke of “structural change”: realigned supply chains, industrial policy, the U.S.–China rivalry, and the fading privilege of the dollar.

Now these ideas have left the seminar room. They define the operating system of the metal world.

What is emerging is not a shock but a drift — a slow and deliberate redirection of industrial gravity.

At its center are the two poles of the new order: China’s pragmatic state capitalism and America’s reluctant reindustrialization.

Each is learning, in its own way, that minerals are not simply commodities; they are instruments of sovereignty.

China’s “anti-involution” doctrine captures this pragmatism well.

It seeks to avoid the waste of internal competition — firms duplicating projects, destroying margins — and to redirect resources toward sectors that reinforce national leverage: renewables, critical materials, electric mobility, and advanced manufacturing.

The approach is unmistakably engineering-minded: design the system, remove friction, and execute.

China is not debating whether to intervene; it is calculating how to optimize intervention.

In the United States, the realization has been slower and more conflicted.

For decades, the country’s economic mindset was juridical — trusting procedure, contracts, and legal predictability over strategic coordination.

That mindset built deep markets but shallow resilience.

Now, through the Inflation Reduction Act, the Defense Production Act, and a growing web of allied frameworks, Washington is attempting something closer to the engineering logic it once disdained: coordinate capital, compress timelines, and rebuild capacity before dependency becomes vulnerability.

Both nations are subsidizing their weaknesses — China to preserve growth; the U.S. to regain industrial competence.

Both are trading efficiency for control, and both now view metals as extensions of statecraft.

This tension was palpable in London.

Copper — the “metal of the transition” — dominated every conversation.

Optimists see structural deficits: over a million tonnes of expected supply have disappeared from the three-year outlook due to operational setbacks in Indonesia, Congo, and Chile.

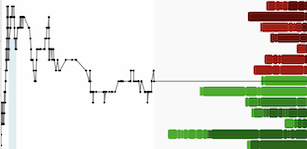

Prices remain above US$11,000 per tonne, and some predict new highs by 2026.

Skeptics counter that the boom in gold and silver — both at record levels — hints at deeper fragility: investors hedging against fiscal strain and the possibility of a prolonged trade war.

Even as the base-metal complex holds firm, Europe’s industrial fatigue and China’s uneven demand suggest a delicate balance.

Beyond the numbers, two signals defined this LME Week.

First, Codelco’s record cathode premiums showed that scarcity now lies not in ore, but in provenance — quality, traceability, and carbon intensity command a strategic premium.

Second, treatment and refining charges (TC/RCs) are under unprecedented stress.

The old benchmark system that balanced miners and smelters is being replaced by a more fluid, bilateral, and politicized market — one increasingly shaped by China’s smelting dominance and Western retreat.

The deeper challenge, however, is upstream.

Mining is becoming slower, costlier, and more contested.

Environmental standards rise, financing tightens, and permitting drifts into paralysis.

At the same time, ore grades decline, haulage distances lengthen, and energy costs rise.

The paradox is glaring: the world demands more copper, nickel, and lithium, yet constructs systems that prevent their supply.

It is a crisis of tempo — a mismatch between political ambition and operational time.

High prices for metals are no longer just reflections of scarcity.

They are signals of strategic compression: the premium placed on reliability, speed, and control.

Gold and silver serve as hedges; copper and nickel as indicators of tempo — how quickly societies can translate geology into sovereignty.

The old market mechanisms are giving way to new architectures of coordination.

Pricing, logistics, and offtake are becoming instruments of policy.

Mining is no longer a story of extraction; it is a story of synchronization.

For countries like Chile and Peru, this is both a warning and a horizon.

Their challenge is not to produce more tons but to integrate into these new networks — to move from being exporters of ore to partners in tempo.

That means traceability, midstream participation, and institutional credibility — the attributes investors now value as much as grade.

The world of metals has entered a new rhythm.

Those who still see it as a market will struggle to adapt.

Those who treat it as an ecosystem of coordination — where engineering, finance, and governance operate in unison — may yet find their advantage.

This article builds on ideas first introduced in Geopolitical Mining: From Ore to Order (QM, 2022) and expanded in Mining Is Dead. Long Live Geopolitical Mining (QM Books, 2025) — where we argue that the next great competition is not for ore, but for tempo: the speed at which nations turn resources into sovereignty.